(Bloomberg Businessweek) — Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez might not have seen eye to eye with Joseph Overton, the late free-market advocate. But she has a firm grasp of the concept for which he is best known: the Overton Window. The term refers to the range of ideas that are at any given time considered worthy of public discussion. Thanks largely to her, the Overton Window on tax rates has just been moved significantly to the left.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) — Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez might not have seen eye to eye with Joseph Overton, the late free-market advocate. But she has a firm grasp of the concept for which he is best known: the Overton Window. The term refers to the range of ideas that are at any given time considered worthy of public discussion. Thanks largely to her, the Overton Window on tax rates has just been moved significantly to the left.

Ocasio-Cortez, the mediagenic 29-year-old from the Bronx, N.Y., is the youngest woman ever elected to the House of Representatives. In an appearance on 60 Minutes with Anderson Cooper that aired on Jan. 6, she was talking up the Green New Deal, a plan to move the U.S. to 100 percent renewable energy by 2035. Cooper challenged her by saying the program would require raising taxes. “There’s an element, yeah, where people are going to have to start paying their fair share,” she replied. Asked for specifics, she said, “Once you get to the tippy tops, on your 10 millionth dollar, sometimes you see tax rates as high as 60 or 70 percent.”

Seventy percent! For perspective, the top rate under the tax law that passed in December 2017 is 37 percent. And now, suddenly, a number so extreme that no one in polite society dared utter it became a focal point of debate. Ocasio-Cortez’s fans—she has 2.4 million followers on Twitter alone—loved it. Some pundits dug up economic research defending rates in the 70 percent range. Others pointed out that Ocasio-Cortez was actually lowballing the historical comparison: Top rates were 90 percent or higher as recently as the 1960s. Defenders of low tax rates heaped abuse on her, which backfired on them by inflaming her supporters.

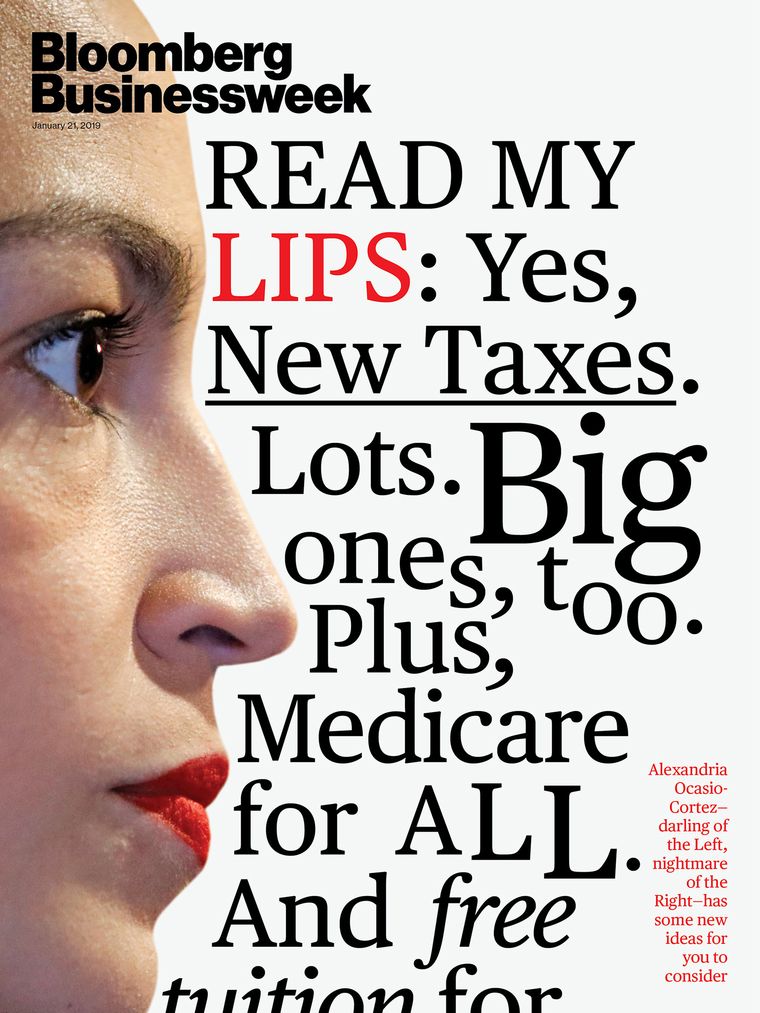

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez Is the Darling of the Left, Nightmare of the Right

What Ocasio-Cortez understands is that getting an idea talked about, even unfavorably, is a necessary, if insufficient, step on the path to adoption. (President Trump also gets this.) “It’s the easiest thing to say, ‘No, we can’t change anything,’ ” says Eric Foner, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian who recently retired from Columbia University. “Most of the big ideas in American history started among radical groups who were told, ‘No, you’re never going to be able to achieve that.’ ” Foner sees parallels between the strategies of today’s left-leaning Democrats and the radical Republicans who fought slavery before the Civil War, “which was put out an agenda, be aware that you can’t just accomplish it all at once, obviously, but change the political discourse by pushing your agenda and then work with those who are willing to do some of it.”

Ocasio-Cortez was actually less radical than she could have been on 60 Minutes. She passed up the opportunity to move the Overton Window on another of her pet issues: budget deficits. She adheres to a doctrine called Modern Monetary Theory that’s catching on among young, left-leaning politicians and older policymakers alike. Its counterintuitive core idea is that deficits don’t matter if you borrow in your own currency, just as long as they don’t cause inflation. Unless the economy is at risk of overheating, MMTers say, paying for a new government program doesn’t require cutting another or raising taxes.

Ocasio-Cortez could have said, “No, Anderson, we wouldn’t need to raise taxes to pay for the Green New Deal. But I want to raise taxes anyway, because I believe in redistributing money from the rich to the poor.” That really would have lit up the internet. Randall Wray, an MMT theorist who’s a senior scholar at the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, wrote in an email that he was “a bit disappointed” that Ocasio-Cortez connected tax hikes to the Green New Deal. Stephanie Kelton, another MMT theorist and Bernie Sanders’s economic adviser during his race for the Democratic nomination in 2016, says she thinks reducing inequality is the real reason Ocasio-Cortez favors higher rates on the rich: “It’s kind of a recognition that levels of income and wealth inequality parallel those of the 1920s.”